People move, commodities move, ideas move, and—maybe more surprisingly—monuments move too. Architecture—in its broadest sense—is mostly regarded as earthed and place bound. In fact, several European languages use words derived from the Latin term immobilis (immobile) to denote real estate. But if we take a closer look, the notion of the immobility of architecture gains fissures.

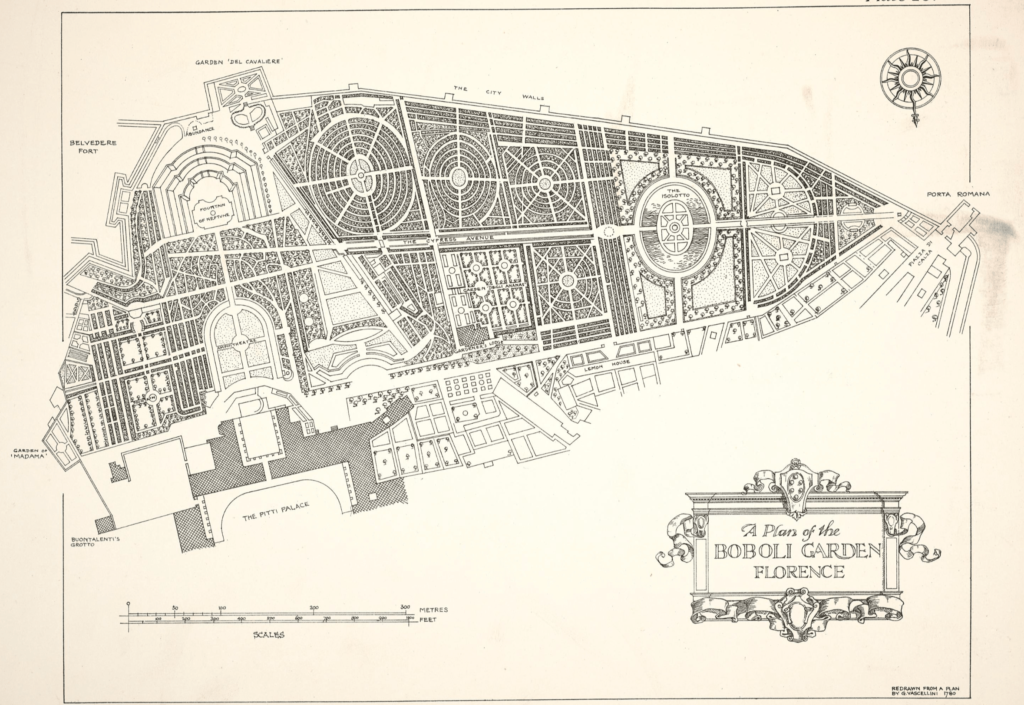

One of the first monuments to catch the eye of a modern visitor to the historical Boboli Gardens in Florence is a 6.23 m high obelisk made of rose granite. It is situated just behind the elongated Palazzo Pitti on a central axis, which reaches from the palace building in the north to the fountain of Neptune in the south. The obelisk, together with a large granite basin, marks the centre of the amphitheatre, which opens on the palace’s back façade.

(© Txllxt TxllxT / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Unlike its bichrome base designed by the Florentine architect Gaspare Paoletti (1727–1813) the obelisk itself is obviously not a product of a modern workshop. The monolith granite block originated from Aswan in southern Egypt and was carved during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II (reigned 1279–1213 BCE). The hieroglyphic inscription adorning all four sides of the obelisk mentions the Egyptian deity Atum who was the chief god of the ancient city of Heliopolis to the northeast of present-day Cairo in Lower Egypt. Therefore, it seems likely that the monument was initially erected in this city, although the original spatial setting remains unknown.

In the late 1st century CE under the Roman emperor Domitian, the obelisk was removed to Rome where it decorated the temple complex of the Egyptian goddess Isis on the Campus Martius, the so-called Iseum Campense. The at times legal acquisition but in most cases violent removal of works of art to Rome was already a well-established practice in the Late Republican period (133–27 BCE), when Roman generals extracted sculptures and other valuable objects from sanctuaries all over Greece. In the case of the Heliopolitan obelisk, the monument was removed from its original context and experienced a change of function in its new setting, although it was fittingly integrated into a sanctuary of an Egyptian goddess. Meanwhile, it can be assumed that most Romans could not read its hieroglyphic inscription—which, however, did not really matter because it was the obelisk’s materiality and specific otherness, in this case ‘Egyptian’ appearance, which attracted the Romans. Not least, the monument in the Iseum Campense was only one of several ancient Egyptian obelisks, some of them also originating from Heliopolis, in Rome.

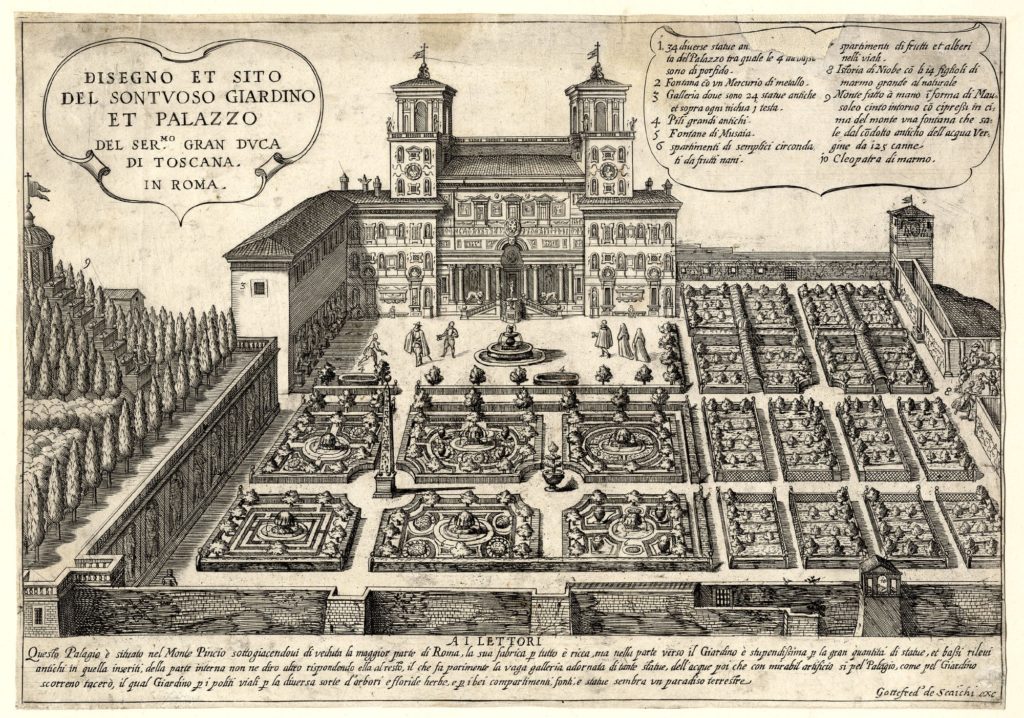

In the 16th century, the cardinal Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1549–1609), an offspring of the famous Renaissance banking family, acquired the obelisk and re-erected it in his Roman villa’s garden complex on the Pincian Hill. In this context, the obelisk served yet another function: the solar symbolism of the gilded orb on top of the monolith as well as the four bronze tortoises fitted into the Medici family’s astrological and political representation. Moreover, the fact that the obelisk was found on the Campus Martius, which—according to legend—had once been in possession of Rome’s last Etruscan king Tarquinius Superbus, was used to propagate the Medici’s ambitions to establish a Tuscan kingship in the region referred to as Etruria in antiquity. Soon, the monument was turned into a fountain, following the fate of other obelisks in Rome.

(© Didier Descouens / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Finally, the Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopold (1747–1792) decided to translocate the obelisk to Florence in the late 18th century. The monument left Rome in June 1788 and was probably shipped from Rome to Livorno where it continued its journey by land arriving in the grand duchy’s capital only in October. One can easily imagine the troubles surrounding the transportation of the heavy monolith—which only bears witness to the high amount of symbolic importance, or, indeed, cultural prestige, ascribed to the Heliopolitan obelisk. Several sites for the re-erection of the monument were in discussion. Eventually in early 1790, the obelisk was set up in the amphitheatre of the Boboli Gardens, taking the place it still occupies today.

Fifty years later, the larger one of two ancient granite basins, which had also been set up in the Villa Medici’s garden complex in Rome, was transported to Florence and positioned immediately north of the obelisk forming a monumental ensemble. The Florentine architect Pasquale Poccianti (1774–1858) planned to elevate both monuments on a stepped, oval foundation assembling them, together with two female bronze figures, into a splendid fountain complex oriented towards the palace’s back façade. However, the project was never completed and modern visitors to the Boboli Gardens are greeted by the provisional arrangement dating back to the middle of the 19th century.

The Boboli obelisk exhibits an extraordinary mobile biography: ancient Egyptian Heliopolis—Imperial Rome—Renaissance Villa Medici—18th century Florence. The ancient Egyptian obelisk was torn out its initial setting and repeatedly inserted in different spatial and cultural contexts which ascribed new meanings to the monument. Meanwhile, the acting persons show a common fascination with ancient Egyptian culture; a phenomenon lasting over many centuries. The movement of the Boboli obelisk through space and time, not least, illustrates that—besides more apparent cases—architecture and architectural monuments can also be mobile, resulting in new spatial constellations and the creative engagement—by fascination with the alien other and/or via absorption into already existing symbol systems—with other cultures.

Further Reading

Capecchi, G. 2003: ‘L’obelisco dell’anfiteatro’, in L. M. Medri (ed), Il giardino di Boboli, Siena, 58–59.

Lembke, K. 1994: Das Iseum Campense in Rom. Studie über den Isiskult unter Domitian, Archäologie und Geschichte 3, Heidelberg.

Parker, J. H. 1879: The Twelve Egyptian Obelisks in Rome. Their History Explained by Translations of the Inscriptions upon Them, 2nd edition, Oxford.