Spanish cultural expression about the Civil War, the Dictatorship and the Transition Period

Spain is a well-known country in Europe for its warm weather, nice beaches and rich gastronomy among other things. But something we don’t see that often on the news is how the society is battle itself about the unstable situation lived during the 20th century and which heir can still be felt in the politics of the country. This situation has impregnated the work of many artists and the cultural heritage of the country that, many times, is debated as it should have been removed.

Historical Context

14th April 1931, Spain declares the Second Republic after democratic elections. This is a period of high political instability.

17th July 1936, Franco began the military coup, and with it, the Civil War. In the war, there were two well-differentiated sides. On one side, the military forces, supported by the right-wing political parties and with the outside support of Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s fascist Italy; on the other, the Republicans, supported by the left-wing, communists and anarchists parties, the working unions and with outside support of communist Russia.

1st April 1939, the Civil War is finished and Franco’s dictatorship begins. This period is marked by a closeness to the rest of the world, even some Spanish participated in both sides of the II World War. A period of prosecution and punishment starts to everyone who didn’t agree with Franco’s laws. Several people are imprisoned and murdered because of political idea, religion and sexual orientation.

20th November 1975, Franco dies, starting a political transition period in Spain.

31st October 1978, the transition period is supposed to be over with the first Constitution since the Republic.

Important Laws on the Matter

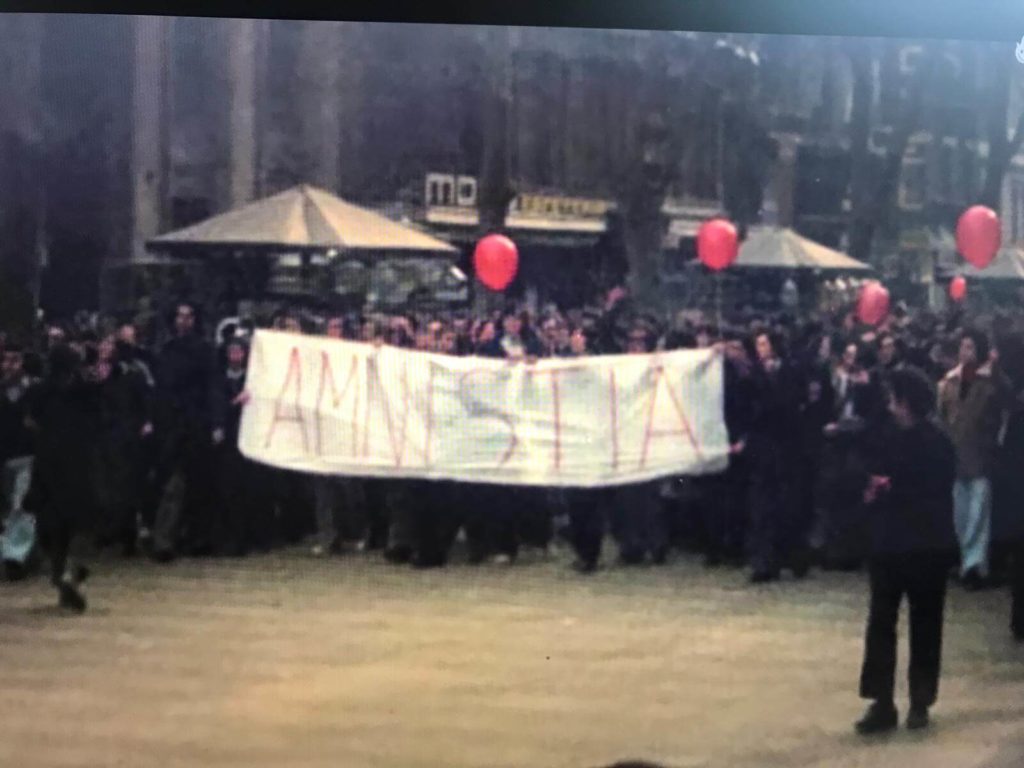

After Franco deaths, all the political parties agreed on the “Oblivion Agreement” to facilitate the transition between the dictatorial and the democratic periods. This agreement meant that everything that happened during the war and the dictatorship would be forgotten and not reflected in the Constitution as a try to advance as a country. In 1977 the government creates the first law referred to the dictatorship, the “Amnesty Law”. This law meant that many prosecuted people in the exile could go back to Spain but also that all the crimes committed by the dictatorship forces would be forgiven and not condemned. The UN has asked several times to the Spanish government to repeal this law.

In 2007 the socialist party, in the government at that moment, approves the “Historical Memory Law” that allows prosecuted people during the dictatorship to ask for amends, the excavation of mass graves by families and petition of Spanish nationality for descendants of Spanish exiled people.

Even then, justice wasn’t always with the victims. Judge Baltasar Garzón was retired from its position after opening a case against crimes committed during Franco’s times. In 2010 many people reunited to start a claim process for the crimes committed against them (torture and imprisonment) or against their parents (murdered) all after the war. This process is still open and is not happening through the Spanish tribunals but from Argentina, where an exiled man started it claiming they were crimes against human rights. Even Argentina justice has asked for the extradition of several people, the Spanish government has denied all of them.

Presently the Spanish government is working in a new law that will be improved the one from 2007 and will be harder on the criminals that committed as well as it will make easier for the families to investigate and recover their relatives’ remains.

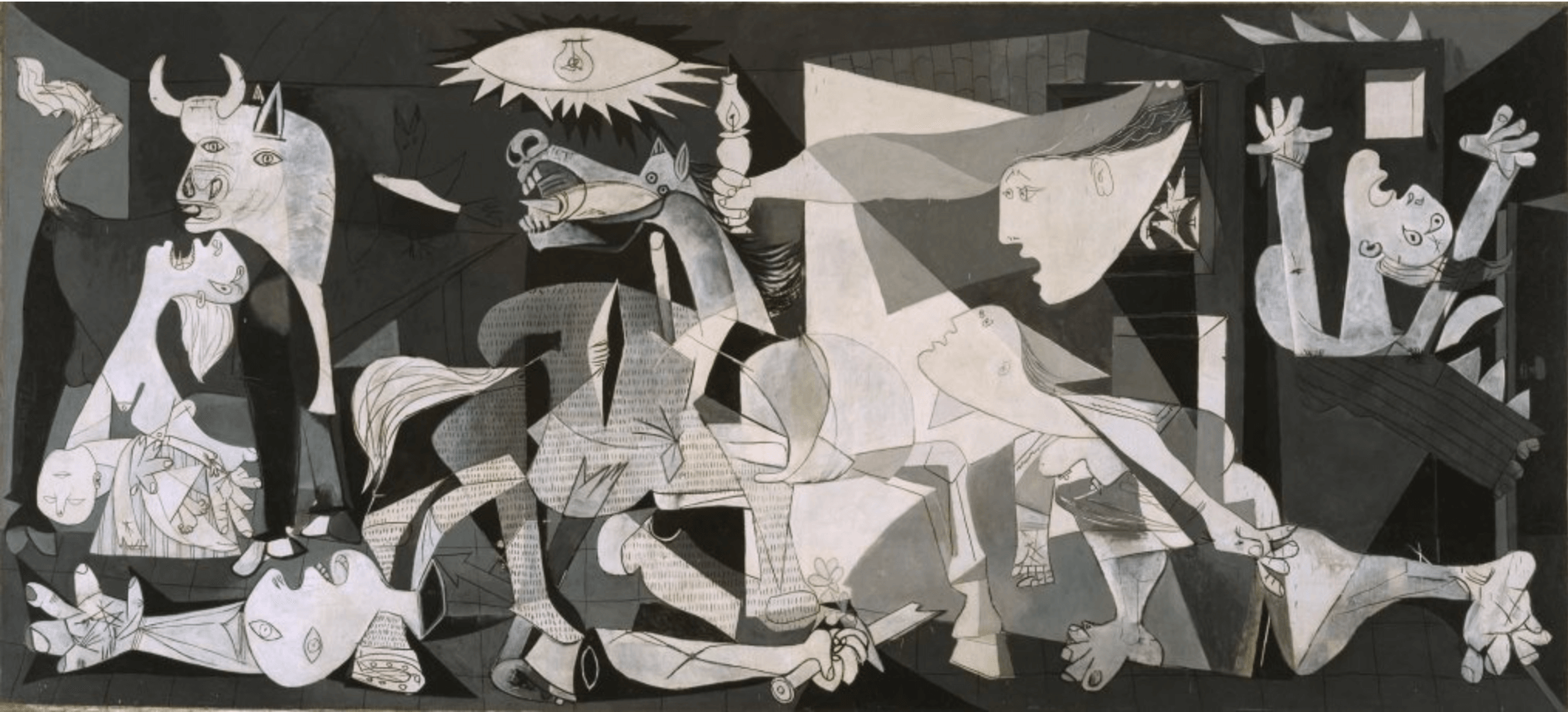

Cultural Expression and Heritage

Since the beginning of the war, the culture was touched by the situation lived in the country. Artists were against, on favour or neutral towards Franco and the rebels and they showed it in their work. As well during the dictatorship and the transition period, the common repression measures made the protest art common. Nowadays, and with the public opinion divided between investigate the crimes and left everything as it was, many artists have taken the goal of showing all of that that was hidden during so long time, many times recurring to the voices of those who suffered it.

Literature

The period before the war was rich in poets. Many authors were congregated in Madrid and from there they created, many times influenced by the French art and the vanguards. Some of these poets were punished during the war or after it. Being two clear examples Federico García Lorca, who was murdered for being homosexual, and which corpse is still missing; and Miguel Hernández, a poet who died in jail during the war for its political opinion.

Many poets kept writing after the war, mostly in the exile in France or Latin America, criticising the situation in Spain, examples of it are Antonio Machado or Rafael Alberti.

Nowadays there is a big range of books in different mediums (essays, novels, comics…) talking about the war or the repression. Examples of these are the comics “The Lincoln Brigade” by P. Durá, C. Esquembre, E. Salguero, that talks about the US citizens that travel to Spain to help the republican side during the war against their own government. Or the comic book “Dr Uriel” by Sento that tells in first person the story of a doctor caught up between sides during the war.

Music

The music related to these periods comes mostly from the end of the dictatorship period (end of the 60s) and the transition period. It continued also during democratic times but with less power than before. The music is marked by singer-songwriters that used their music to ask for justice. It was also really common for them to adapt to music poems of the death or exiled poets. Great names are Paco Ibáñez, Raimon (who sang in Valencian, forbidden during the dictatorship), José Antonio Labordeta, Luis Eduardo Aute, Joan Manuel Serrat…

Movies

Most movies that talked about the war or Franco’s regime portrayed it nicely, not facing the power. Between the directors of this time is worth mention Luis García-Berlanga who talked about the war in his movie “La Vaquilla” (The heifer) or about the money received from the USA with the Marshall Plan in “Bienvenido Mister Marshall” (Welcome Mr Marshall).

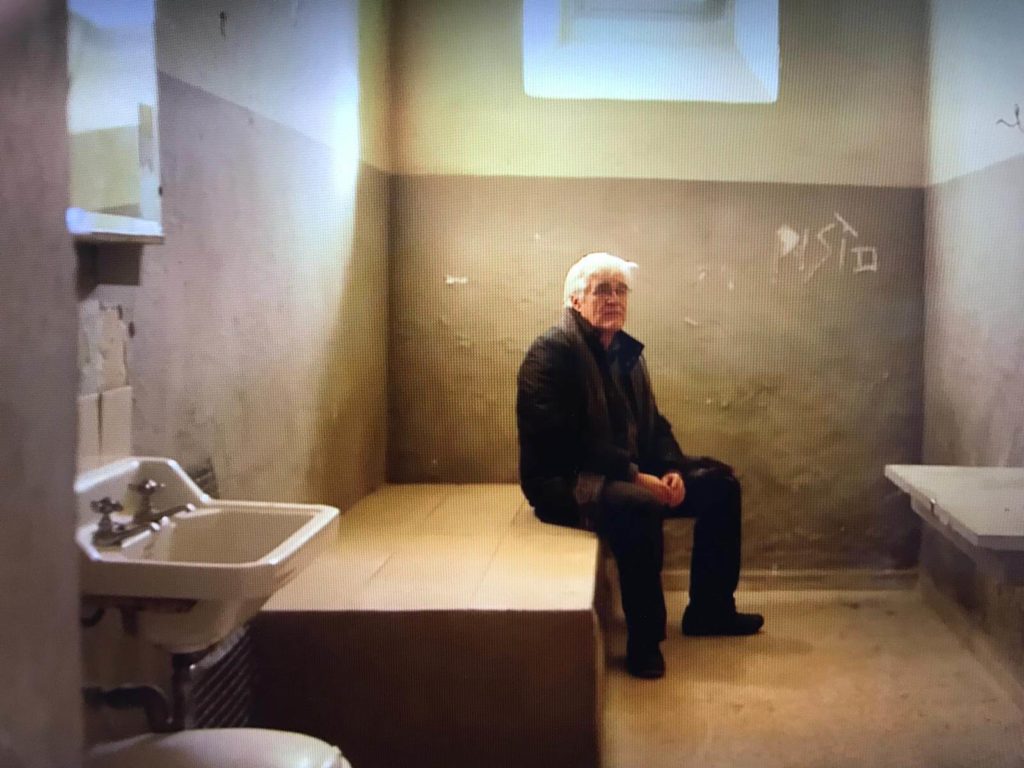

Nowadays authors have become more critical about it. “La Voz Dormida” (The Sleeping voice), B. Zambrano, 2011, talks about two sisters, one pregnant and in jail for her political ideas, the other fighting to get her sister out of the jail. But not only fiction movies have become more common, documentaries talking about the experiences lived in the first person are becoming more common, and show the experience of many people that has to live with the suffering from their past seeing how the justice does nothing for them, this is the case of the famous award-winning documentary “El Silencio de los otros” (The Silence of the others), A. Carracedo and R. Bahar 2019.

Also, this period and the repression suffered within it is portrayed in mainstream series as “Las chicas del cable” (Cable Girls) and “Alguien tiene que morir” (Someone has to die). Franco’s dictatorship is not the main story on none of them but it is present and creates a tense atmosphere for some of the characters that influenced the story.

Monuments and Sculptures

Many monuments to Franco’s figures and ideology were created during the dictatorship. Since 2010 with the start of the Argentinian claim and the raised of left parties in charge of municipal councils and autonomic governments, many of these symbols and monuments have been removed from the place, leaving us with the question what to do with them?

Some monuments which didn’t represent the dictator directly have been maintained, same as the building that was built or used for oppression, that, simply changed its function, leaving also the dilemma if changing the function erase the symbology.

Since 2007 and with the first regulatory law, many towns or regions with common burials have created monuments dedicated to their lost people. In the case of massive murders, some cemeteries have added plates remembering the name of the falling ones.

Archaeological Remains

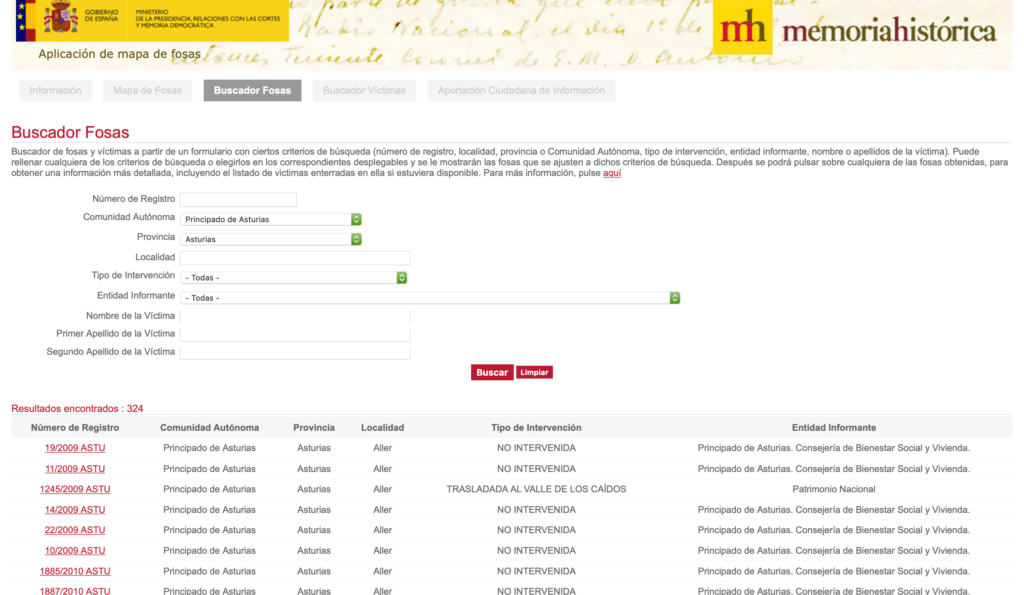

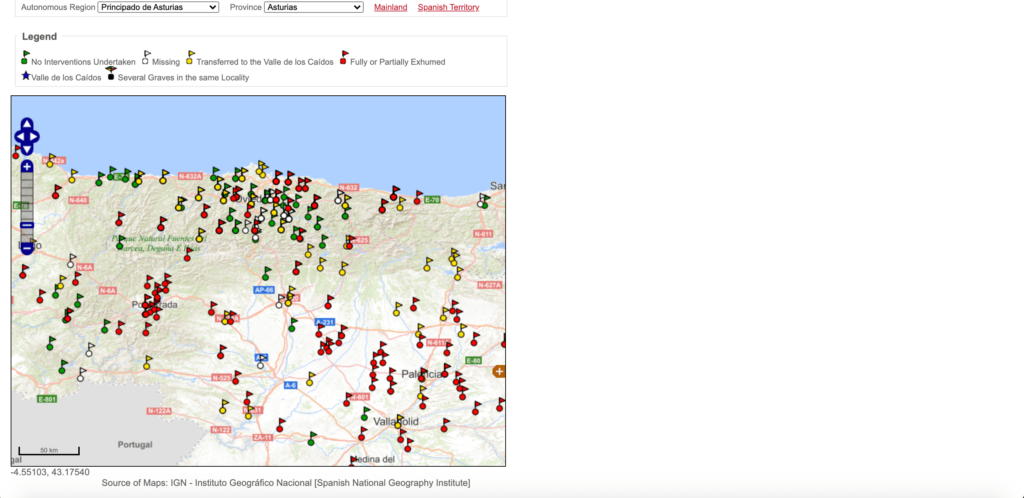

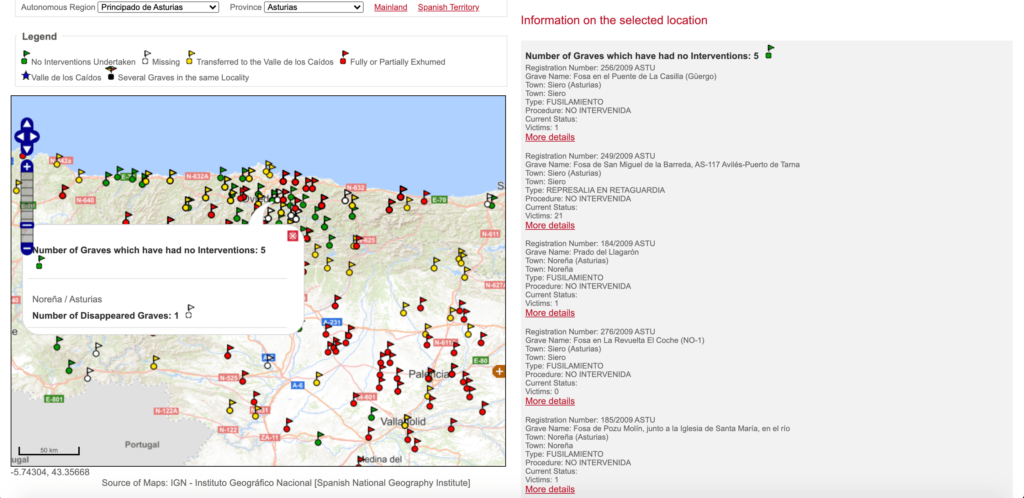

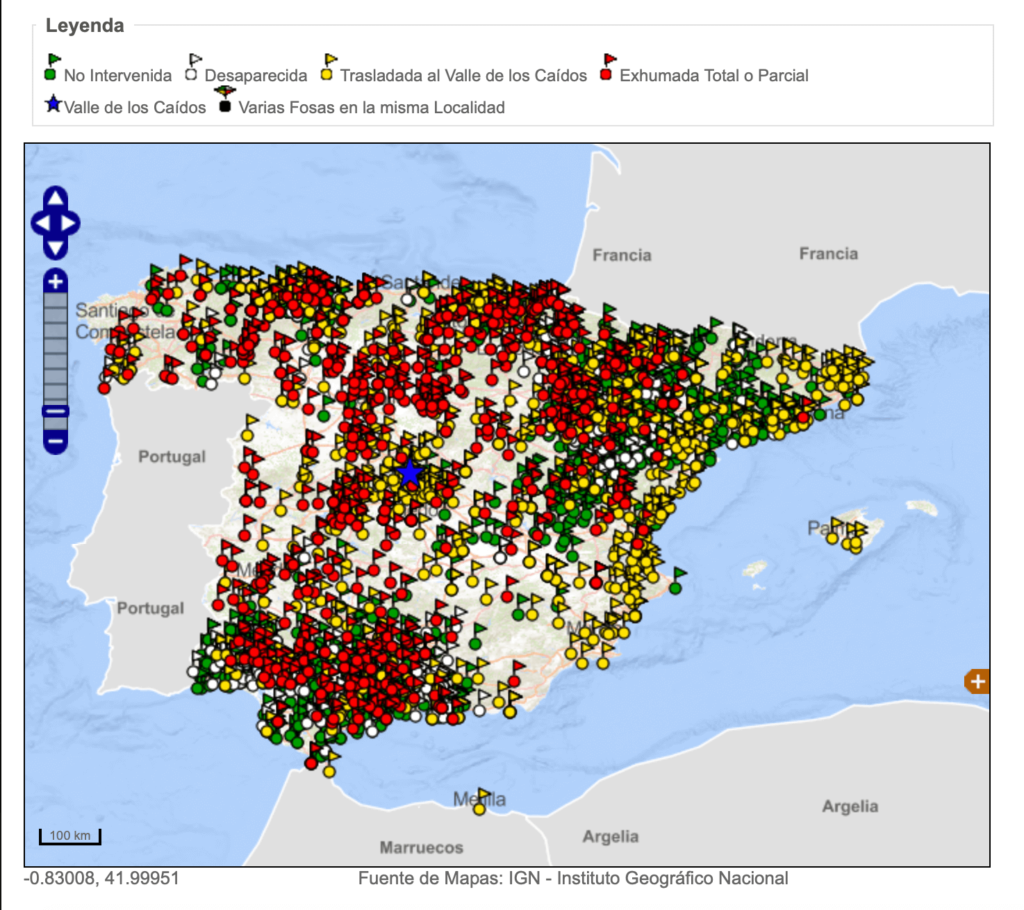

The common burials that have been excavated since the 2007 law have to follow archaeological excavation procedures as they are part of the country’s heritage. The Government created an online map that shows the known burials with their current state and some more information about them, when possible. The new proposed law proposes a forensic archaeologist as director of these procedures as a warrant of a good praxis.

Final Consideration

The heritage of the 20th century in Spain is a delicate topic, as it is the history of the country. A Civil War confronts people from the same family or town, siblings, neighbours and friends were forced to fight, many times just depending on their geographic location more than on their political ideas; and sadly, the violence in Spain didn’t finish once the war ended.

The topic of the Civil War, Dictatorship and Transition period’s heritage still divides the population, some don’t want to touch injuries that on their eyes are healed. For others, the injuries are as open as always and just want justice.

Spanish society still has a long path to walk, but hopefully, more and more voices will be heard and we would be able to learn more about those periods and how to treat their heritage.