By Lianne Oonwalla, an Indian student in Germany.

Welcome to the first chapter of a two-part story celebrating the season’s favourite theme: Spooky!

Double, double toil and trouble;

– Song of the Witches, Macbeth by William Shakespeare

Fires burn and caldron bubble.

Cool it with a baboon’s blood,

Then the charm is firm and good.

Describe a witch in 5 words: warts, old, flying, scary, evil. Easy, right? The quintessential witch is often associated with these words and other similar descriptions. Pointy hats, warty noses, green-tinged skin, and cackling wildly as they toss their latest sacrifice into a bubbling cauldron…this is the image of a witch often described in fairy tales and folklore. Early witches were thought to be devil worshippers and practitioners of dark magic who called upon spirits to do their evil will. Of course, pop culture has its own definition of modern witches: awkward teenagers grappling with new-found powers and fighting evil, powerful witches masquerading as housewives and ordinary, rule-abiding college students with deadly secrets. This stereotype of witches and witchcraft have been reinforced into memory throughout history as characteristics passed down through the centuries in various different forms. The true history of witchcraft is in reality a lot darker than we know.

The Early Witches

Etymologically, the word witch derives from the Old English word wicca

(male sorcerer) and wicce (female witch). No consistent definition of the word exists yet, rather just interpretative descriptions that have attached themselves to the word over the centuries. Early witches, both male and female, were believed to be people with supernatural abilities who used magic, spells and sacrificial rituals to summon spirits or bend circumstances to their will. Later definitions painted them to be in cohorts with the Devil, resorting to cannibalism and engaging with the forces of evil. The word witch also attached itself to ‘wise women’, or healers, who’s aptitude for curing illnesses was misunderstood as magical and inexplicable healing powers.

Witches soon earned a reputation for being evil practitioners of the occult and dark magic, using potions, spells, and supernatural abilities to do their bidding. Although defined differently in a myriad of literature and context, witchcraft has generally been regarded as the work of crooked old women who met late at night under the cover of darkness to perform dark magic and release evil into the world. Though existing more as a fantasy than factual reality, this definition has a long history that can certainly be held responsible for the bad reputation placed on witches and their craft. The witch hunts that ravaged Europe between the 14th to 18th century with hundreds of often innocent people sentenced to death is one of many testaments to how dangerous a negative stereotype can be. The history of witchcraft is certainly an intriguing topic to dive into, but one will find that it was a deadly period for witches.

History.com quotes one of the first appearances of witches in writing in the Bible’s Book of First Samuel. “Thou shall not suffer a witch to live” , Exodus 22:18, is just one of the Bible versus that condemns witches and witchcraft. Their bad reputation, created and spread as early as the 11th century, gave way to widespread witch hysteria in 14th century Europe. In fact by the 15th century, writers often used the Latin word maleficus to mean witch, maleficium being the practice of harmful acts on or against other human beings. Stories of their horrific deeds spread quickly, and stirred up the vilification of witchcraft in medieval European society.

The European Witch Hunts

The European witch hunts ravaged a majority of the continent between 1400 and 1800, leaving behind a bloody legacy and over 40,000 people executed for practicing witchcraft. Witch-fever as it is called, led to the mass murdering of suspected witches, mostly women, believed to be consorts of the Devil and engaging in his malicious deeds. Witches were blamed for a variety of strange natural phenomena like bad weather, dying crops, famine, and other disasters that were unfortunately quite frequent at the time. It was believed that their “evil deeds” brought the wrath of the gods down to earth, and they were often blamed for natural occurances like lightning storms and heavy rain.

Where did this stereotype of evil witches originate from? One article attributes this sudden turn to travelling friars from the Swiss Alps in the 1420s. Their mission was to thwart heresy in local communities. During the course of their task, they gathered stories and local encounterings of witches and reported it back to the authorities, who then recorded their retellings: accusations of witches slaughtering children, riding flying broomsticks smeared with murdered baby fat to secret meetings late at night, cohering with the Devil and his Satanic sects, are all derivative from local folklore, and it was to these acts that accused witches on trial often confessed to. These stories spread quickly throughout Europe, leading to witch hunts and tortures. The regions between France, Germany and Switzerland witnessed the majority of killings during this terrifying period.

14th century Europe was perhaps the unfortunately-perfect catalyst for spreading witch-hysteria. Brimming with Christian ideologies, propelled furiously by the Church, the society of the time was gradually Christianized. Protestantism was on the rise as a direct opponent of the Church’s religious authority, resulting in a race between the two ideologies to attract more followers. The fear of witches and witchcraft was a useful driver for conversions and attracting more followers. An interesting theory suggests that from a more economic standpoint, the European witch trials indicated a “non-price competition between the Catholic and Protestant churches for a religious market share in confessionally contested parts of Christiandom.” The theory suggests that the two battling branches of the Church were each vying for the attention of the religiously undecided individual by capitalizing on their fear of the occult, assuring them that if they followed a certain path, and that path only, they would receive protection from the forces of evil (read: witches) and eventually earn their Salvation in Heaven. Witchcraft and Satanic cults became synonymous terms, resuting in widespread hate rooted in the general fear of the inexplicable.

The Hunt Continues

This irrational fear and hate lead to the hunting, torturing and execution of those believed to be practitioners of the dark arts. Witchcraft was immediately condemned as heresy, and several innocent people confessed under torture to murders they never committed and were sentenced to death for crimes they were often falsely accused of. Between 1400 to 1782, almost 80,000 people were tried for witchcraft and half were sentenced to death for practicing it. Witch fever spread like wildfire, spurred on by theologians writing literature and handbooks on eradicating witches. The Malleus Maleficarium (The Hammer of Witches) is one of the well known disquisitions on witchcraft. Composed in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer, it was a handbook on the capture, torture and execution of witches. It dictated the horrfic standard procedures for dealing with witchcraft, especially popular among Catholics and Protestant communities, soon becoming the second fastest-selling text of the 14th century, bested only by the Holy Bible.

Witches were “identified” by Devils Marks – warts, moles or any strange marks found on a person´s body that were deemed suspicious were poked and prodded with sharp instruments under the claim that if touched by the Devil, these pricks would not cause the accused any pain. Swimming was another test conducted on suspected witches; they were forced into bodies of water and if they sank they were “innocent” but if they floated they were “guilty”. Witchcraft was not considered a crime only by the Church; ecclesiastical and secular courts were equally responsible for witch trials throughout Europe, with law and justice playing an important role in the squashing out of any occult practices. In the 1560s witchcraft was made a capital offence in Britain. The year 1645 to 1646 in region of East Anglia saw a steep rise in witch hunts and killings, led mainly by a lawyer named Matthew Hopkins. His reputation for capturing and executing witches earned him the title of Witchfinder General. By the end of this period Hopkins was responsible for about 600 killings.

A Bloody End

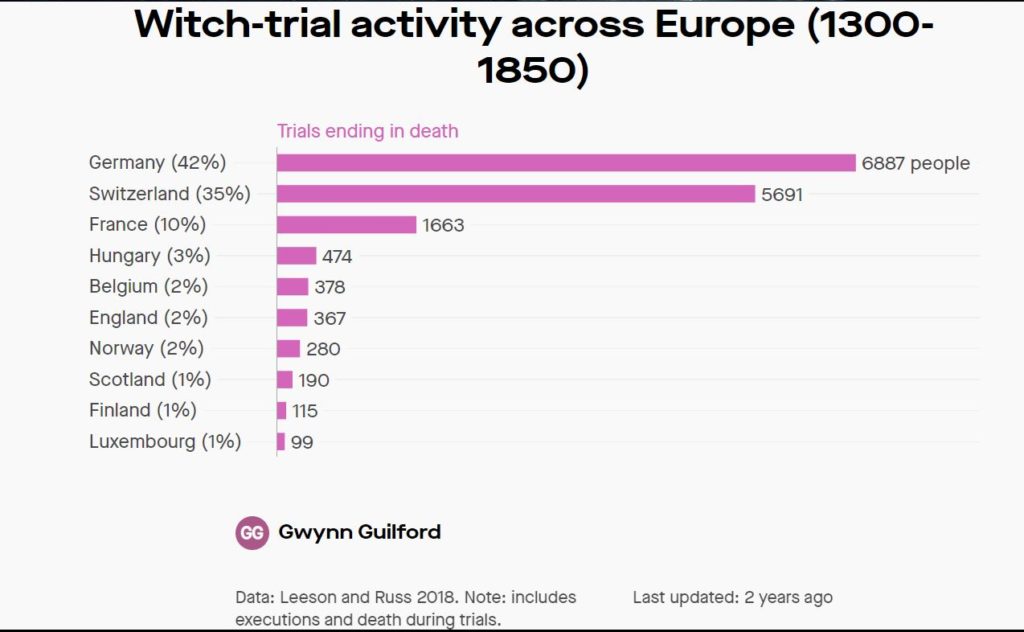

Northern parts of Europe were particularly bloody battlegrounds during these years, with more than three-fourths of witch trials taking place in Germany, northern Italy, Switzerland and France, during the time religious prosecution in these parts was at its fiercest. Contrastingly, studies show that countries with an existing Catholic hold and fewer prosecutions were much less inclined towards hunting any potential witches; Spain executed only 12 suspected witches and Portugal no more than 7. Witch hunting in Britain continued well into the 18th century despite several governmental Acts against witchcraft being repealed by then. Finally, in 1782 Switzerland had tried and executed its last alleged witch, thus bringing the European witch hunts to it’s end.

The reasons for the gradual dying out of these feverent witch hunts may be explained by the arrival of a centralized judicial system known as the Inquisition. The hunting and torturing of alleged witches was outlawed and witchcraft was decriminalized – but history is still unable to agree on a reason for the widespread massacres. They cannot fully be attributed to gender discrimination despite the fact that most witches were considered to be women, nor can they be fully blamed on political or religious agendas or rising economic pressures. Witch hunts seemed to have disappeared into the abyss as easily as it appeared, by the late 16th century, witch-hunting in Europe came to a grinding halt. However, it should be noted that the murderous attitude towards practicing witches was on a steep rise across the oceans in America. In 1692 the infamous Salem Witch Trials began in Salem, Massachusetts, instigated by a few townswomen who claimed to have been possessed by the Devil. They accused several village women of witchcraft and stirred up another bout of witch-hysteria in the region, leading to the trial and execution of over a hundred men, women and children. Trials continued until 1693, until being declared unlawful by the Massachusetts General Court in 1697.

Wicca and the Modern Witch

Witchcraft was soon discarded as primitive thought by modern thinkers, but it prevailed in modern society despite its gradual stamping out. Modern witches are mostly practitioners of Wicca, a predominently Western, pre-Christian tradition of nature worship created in the 1950s. They worship the Goddess, practice cermonial magic and celebrate Samhain (a modern reflection of ancient Celtic religious practice of the same name) and important natural phenomena. A rise in general religious tolerance, with focuses shifting to individual subjectivity and expression, feminism and even the rise of interest in fantasy literature has made it possible for Wiccans and their craft to be practiced in a safe space. Wicca is now a recognized religion with many sub-branches, attracting several new followers every year. Aspects of the movement such as Tarot card readings and everyday charms have become popular, with other traditions and practices also prominent in today’s society. The inclusionary stance that is now rightfully taken by many modern religious communities has made it possible for Wicca to be an accepted form of modern religious expression. It should be noted that Wicca and Witchcraft are not synonymous. Wicca is a religion, and Witchcraft is a practice; not all Wiccans are witches and not all witches are Wiccans.

“To reclaim the word witch is to reclaim our rights, as women, to be powerful. […] To be a witch is to identify with 9 billion victims of bigotry and hatred and take responsibility for shaping a world in which prejudice claims no more victims.”

– Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, 1979

The quote above is from one of the most popular books on modern Wicca and its ties to feminism, written by Starhawk, an American activist and teacher. It may be argued that modern Wicca has a touch of feminism or female empowerment attached to its appeal, and rightly so, considering that the major crimes and murders of the 14th century witch hunts were directed towards women. Emphasis on modern witchcraft is placed on healing, natural energies especially centred arond the moon, and embracing female power. The movement has seen a resurgence especially from young, open-minded and politically-engaged women.

Upon reflection, the 5 words used to describe a witch may now be very different, perhaps: powerful, energetic, knowledgeable, worldly, creative. Well, these and a whole lot more!

This was part one of a two-story feature on October’s favourite theme: Spooky! Stay tuned for part two, coming soon to a Spookfest near you!

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX