By Lianne Oonwalla, an Indian student in Germany.

My fascination with the concept of time began at a young age, having grown up reading a lot of sci-fi, space and time-travel literature and obsessively binge-watching (and re-watching) episodes of the classic British TV show Doctor Who, about an alien Time Lord that visits different planets and travels in time. The idea of “time”, as I learned through these fictitious works therefore seemed rather fluid to me. The more I learned, the more I wanted to question it. Does time move differently for other people than it does for me? Who even invented “time”? How do I know if five minutes for me feels the same as five minutes does for someone else? How do I even begin to describe what five minutes “feels” like? What about when you take a flight from one time-zone and end up landing in a whole other time-zone that’s four hours ahead of the one you just left…is that time-travel? WAIT A MINUTE…DID I JUST TRAVEL IN TIME?! If you’ve ever had your head explode with meta (sorry, I am a millennial after all) questions like these, then let me assure you, you aren’t alone.

How the ancients perceived time is as unique as the inventions they used to measure it. The Judeo-Christian belief that time is linear can be derived from the book of Genesis: “And God said, “Let there be lights in the dome of the sky to separate the day from the night, and let them serve as signs to mark sacred times, and days and years, and let them be lights in the dome of the sky to give light on the earth.” This explanation led them to believe that day is always followed by night because that is how it was created.On the other hand, the Mayans kept track of time with three different calendars, most notably the Long Calendar responsible for the 2012 apocalyptic predictions, and marked the passage of time and major events with glyphs. The ancient Greeks understood time as two different concepts – Chronos or chronological time and Kairos – metaphysical or “Divine” time.

Temporal heritage

So how did our ancient predecessors keep track of time? We know they measured time by the sun, moon and stars as well as by natural seasonal changes. In fact, Britannica.com records the earliest instrument used to measure time was a vertical stick called “gnomon”, who’s length of shadow was used to indicate the time, all the way back in 3500 BCE. We know the ancient Egyptians invented the first sun-dials, known as “shadow clocks”, dating to around the same period; and the Mayans invented one of the earliest known calendars. Early humans in what is now central Europe measured the passage of time by carving the movements of the sun and moon into mammoth tusks. Water clocks known as clepsydra (believed to be invented in ancient Babylon) were used extensively in ancient Greece, where the earliest-known clock with a water-powered escapement (i.e. mechanically geared clock that runs on the energy generated by running water) was also invented as early as the 3rd century BC. Neolithic structures were built by our ancestors to measure time – Stonehenge, for example, was used to track the midwinter solstice and welcome the new season.

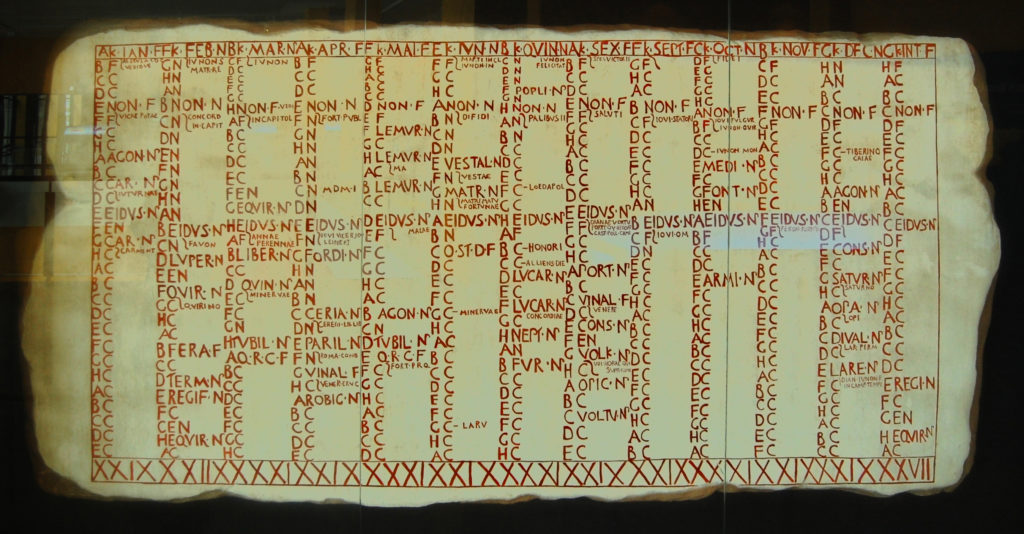

Time has for thousands of years also been used a powerful political tool. Let’s have a look at the Roman Calendar, invented by the Roman kings Romulus and Numa Pompilius for an example. This calendar wasn’t very accurate and needed to be recalculated quite often to keep up pace with the lunar year. With the establishment of the Roman Republic, the calendar was exploited by the pontifices and years were often re-dated or altered to lengthen the ruling term of the (then) current leader. Its successor was the Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar, was invented as a solution to the discrepancies of its predecessor. However it was also flawed and was soon replaced by the Gregorian calendar, named after its inventor Pope Gregory XIII, and this is the calendar still used today. It was invented to balance out the flaws of its predecessors.

The first mechanical clocks were invented in Europe in the early 14th century, such as the Astronomical Clock of Prague, designed in 1410, making it the third-oldest clock in the world and the oldest clock that is still operational. Mechanical clocks were the standard instruments used to measure time until the mid-1600s when the pendulum clock was invented, and by the 17th century pocket-watches became fashionable. A post-World War Two Europe witnessed the invention of the atomic clock and eventually the arrival of quartz clocks that became the primary time keeping instruments around the world, and have remained so since then.

Over the millennia our time-keeping abilities have been honed to absolute precision, enabling us to track time down to the last second. Today, temporal measurement takes two familiar forms: the calendar – a “mathematic measurement of time divided into intervals” and the clock – a “physical mechanism used to measure the hourly progress of time”. Atomic clocks are currently the most accurate measure for time, able to track its passage to a millionth of a second! The world as we know it is now divided into intercontinental time-zones, and in some cases these time zones differ from each other even within the same country. Who invented this system, and why?

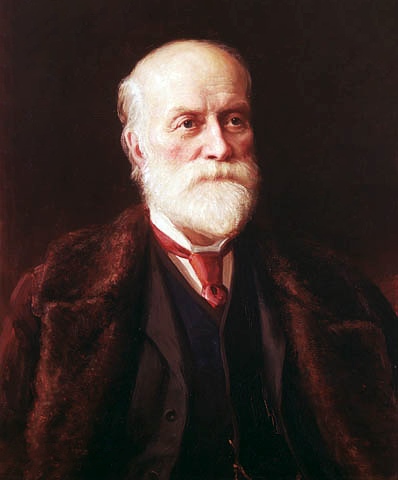

The original Time Lord

The invention of the coordinated universal time (UTC) can be attributed to Scottish-Canadian engineer and inventor Sir Sanford Fleming, and was globally adopted in 1884. Fleming’s system identified the solar time in Greenwich, a town in England, as a measure for a standard timescale. Thus world standard time was created, and gradually our world was divided into 24 time-zones, each defined from the solar mean time in Greenwich.

Fleming journey to the invention of the UTC is an interesting one. As the story goes, he confused a.m for p.m, and a frustrated Fleming missed a train because of a mistake that is ironically still made by many a weary traveller!

Fleming proposed the creation of a standard universal time, with “hourly variations linked to a system of different time zones” for different countries. This system would be based on the Greenwich meridian, which was believed to be at longitude 0. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was used extensively by the British navy and railway system since 1847 and was considered a local measuring system, until the idea was proposed by Fleming to the International Prime Meridian Conference in 1884.

The industrial revolution and cross-country train travel ushered in the need for a greater agreement of the passage of time – a universal measure to track commerce and trade movements within Europe and to assure a modern functional society. A time standard that suited the entire world and allowed for free movement between continents was the dire need of the hour. This sprouted the development of the modern UTC – a collaboration of 41 nations – signed at the conference in 1884, making the solar time taken at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England the definition of the “universal day”, calculated from (Greenwich mean) midnight. The rest as they say is history.

As the saying goes: Time and tide wait for no-one

Researching the origins of time and time-keeping is as overwhelming as attempting to understand our perception of it. Let’s stick with the facts for now – time as we know it moves like a river, it flows in a linear trajectory and it can be measured. It exists in our physical world as a fourth dimension but in itself has no physical form. It is experienced differently by people in different countries. As I write this it’s 20:28 in Berlin and I’m enjoying a sunny evening on my couch, but it’s also 23:58 in Mumbai, and my parents are in bed enjoying an episode of “Breaking Bad”; so really who’s to say what time it actually is – I guess perception is everything.

Whether time is a human construct or a phenomenon that has existed since the inception of the universe itself is certainly a topic for us to debate for the rest of our lives. All I know for sure is time moves incredibly fast, and I would like to use it as effectively as possible to live a happy life, possibly or rather, most definitely filled with research on time travel and how I, as an ordinary citizen of the world, can contact a mysterious Time Lord with a big blue box for an adventure in space and time. So if you’re reading this, dearest Doctor…it’s the 14th of September 2020, and at 20:38 I’ll be waiting for you on my balcony in Berlin. Don’t be late!

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX