Every day I take a walk through the center of my home city, Bologna, and pass in front of our big basilica, San Petronio. It proudly dominates the iconic main square, Piazza Maggiore. However, San Petronio looks a bit strange. Its facade is divided in two parts: the lower half covered with marble, the upper half made of bricks. People visiting Bologna often ask mewhy the church was built in a such way, and they are surprised to find out: “Well… They just ran out of money”.

It looks like people can’t believe that the construction of such lofty monuments could be affected by such mundane problems. But, actually it happened for many of the beautiful ancient churches we admire across Europe, many of which took centuries to build. This is also the case with our basilica, but ours was never finished. San Petronio was a troublesome object, a symbol of the complicated relations between Bologna and the Papal States, of which the city was part from the Middle Ages until Italian Unification in 1861.

Though it was never the capital of a state, fourteenth-century Bologna was one of the richest and most populous cities in Europe. Europe’s first university, and a lucrative silk market made Bologna into a thriving metropolis. The enormous wealth it generated helped build a unique skyline of tall towers, not unlike modern cities. Bologna already had its own cathedral, San Pietro, but city leaders wanted more. They wanted Bologna’s church to be bigger than Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The church would be dedicated to the fifth-century patron of the city, Petronius, and owned by the citizens, not the Church.

In its current incomplete form, San Petronio is among the ten largest churches in the world, and the largest made of bricks. Sixteenth century plans made the basilica the biggest on earth, but jealous Popes always stymied progress on the immense work. For example, Pius IV financed the construction of the new university complex (the Archiginnasio) only twelve meters away from San Petronio, de facto stopping its enlargement.

Today, the basilica still stands unfinished and its shape looks somewhat “mutilated”, especially on the two sides where the naves seem cut by a knife. Notwithstanding it was one of the European wonders in the Renaissance, and it gained huge notoriety when it was chosen by Pope Clement VII himself as the place to crown Charles V Holy Roman Emperor in 1530. It was also decorated by some of the finest artists of the time: the sculptures by Jacopo della Quercia on the main gate were used as a model by Michelangelo for his works. Michelangelo also worked in San Petronio, making one of its lost masterpieces, a huge bronze statue of Pope Julius II. Unfortunately, an angry mob destroyed the work in 1511. Complicated relations…

An artwork also caused some troubles that were unexpected when it was painted. One of the chapels hosts a fresco by Giovanni da Modena, which shows scenes of the Last Judgement. In its horrific depiction of Hell, a gigantic Lucifer dominates the work. The prophet Mohammed also appears being devoured by a demon. After the September 11th attacks, Italian police have thwarted several Islamist terrorists attempting to damage or destroy San Petronio. The main staircase of the church used to be a a beloved meeting point for citizens, but it has remained closed for security reasons for many years.

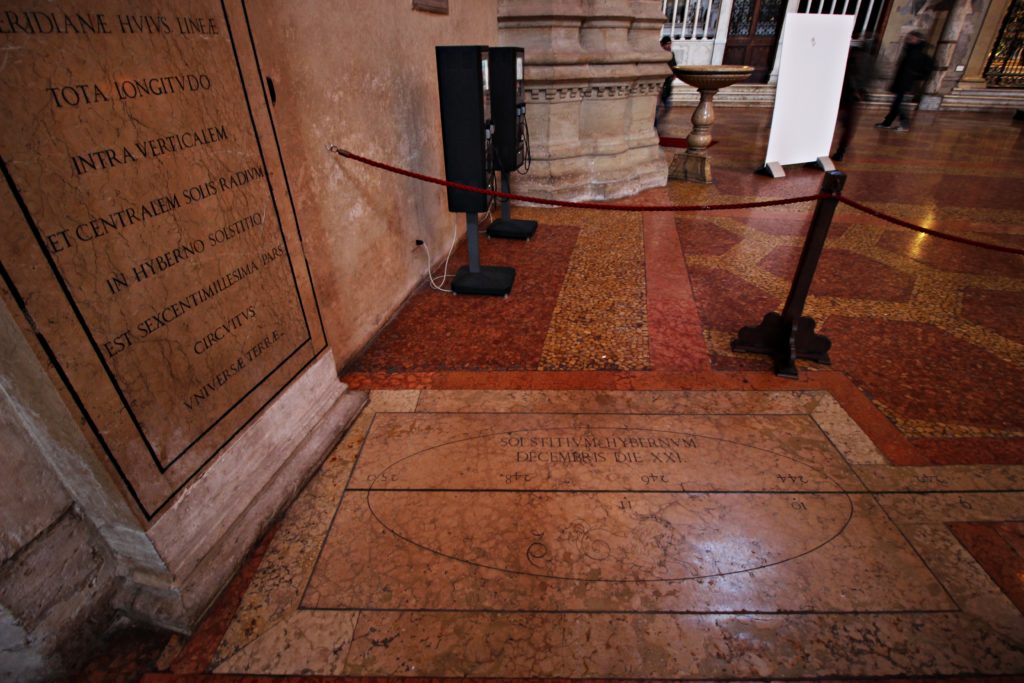

Not only art enthusiasts, but also science freaks are welcome under the grandiose Gothic naves of San Petronio. On the floor you can admire the biggest meridian line in the world, designed by the well-known astronomer Giovanni Cassini. In the mid-seventeenth century Cassini taught astronomy at the University of Bologna and was commissioned to create a new line to replace a previous one made in 1576. This gigantic time device, 67 meters long, was completed in 1657 and gained immediate renown in the scientific community that lasts until today. Recent examinations showed that this meridian is still accurate in setting the day of the year.

San Petronio remained in the hands of the city until 1929, when it was taken over by the diocese. It still remains the most important church in Bologna, much more than the official cathedral in the feeling of the community. Its history reflects the strong sense of rebellion and independence that Bolognese people pride themselves. Not much has changed in the last six-hundred years.